L. A. Counterfactual: How the City's Architectural Development Might Have Been Different

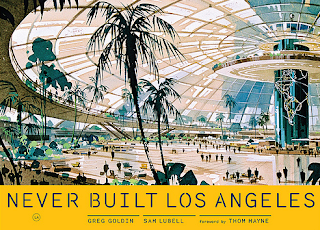

I was recently in Los

Angeles and stopped by the fascinating new exhibit, “Never Built Los Angeles,”

at the Architecture and Design Museum on Wilshire

Boulevard.

The exhibit profiles dozens of architectural and

city planning projects that came close to being realized but ultimately failed.

Gazing at the drawings and models of the

proposals, one cannot help but feel many of the feelings that underpin all

counterfactual speculation: regret that about opportunities missed and

gratitude about disasters avoided.

Some of the tantalizing proposals that might have

made the city more architecturally grand appeared in the 1920s and 1930s,

including a City Beautiful plan along Wilshire Boulevard featuring arches and

fountains and a massive Art Deco civic

center complex designed by Lloyd Wright.

At the same time, we can be grateful that

many ill-considered proposals came to naught. These include Richard Neutra’s mega housing development for

30,000 people in Chavez Ravine, a 1965 plan for an offshore freeway, called the

Causeway, running through Santa Monica Bay, and a bland assemblage of

generic skyscrapers on Grand Avenue in Downtown.

Like all good counterfactual history, the exhibit also sheds light on the forces of historical causality, making clear that Los Angeles’s missed architectural opportunities have usually stemmed from the greater power of private interests (developers, mostly) compared to city political officials.

As LA Times architecture critic,

Christopher Hawthorne, put it in a recent review: “The city…has both inherited and refined over

many decades a political system that makes it far easier to say no, to protect

the status quo and pockets of wary and litigious privilege, than to advance an

agenda for positive change.”

As a result, the city has shown great timidity in the realm

of civic minded public architecture at the same time that it has displayed bold innovation in the realm

of private building (mostly residential architecture).

In the end, the exhibit prompts us to wonder what might have been. To quote Hawthorne, "[had some of the visionary public projects] been

completed, the character of Los Angeles would be strikingly different. It would

be a more public-minded, greener and perhaps a more equitable city than it is

now.”

Comments

residential architecture Beverly Hills

architects los angeles